Surgery that helps move beyond survival

Dr. Luc Mertens helps patients born with complex heart defects to live better, for longer

Chapter 1 Different hearts

When a baby is born with just one pumping chamber (functional ventricle) in their heart instead of two, it affects their health for life. This is called a univentricular heart, and it’s one of the most complex congenital heart defects.

Now, thanks to medical research and surgical innovations, that baby is likely to live well into adulthood and even senior years.

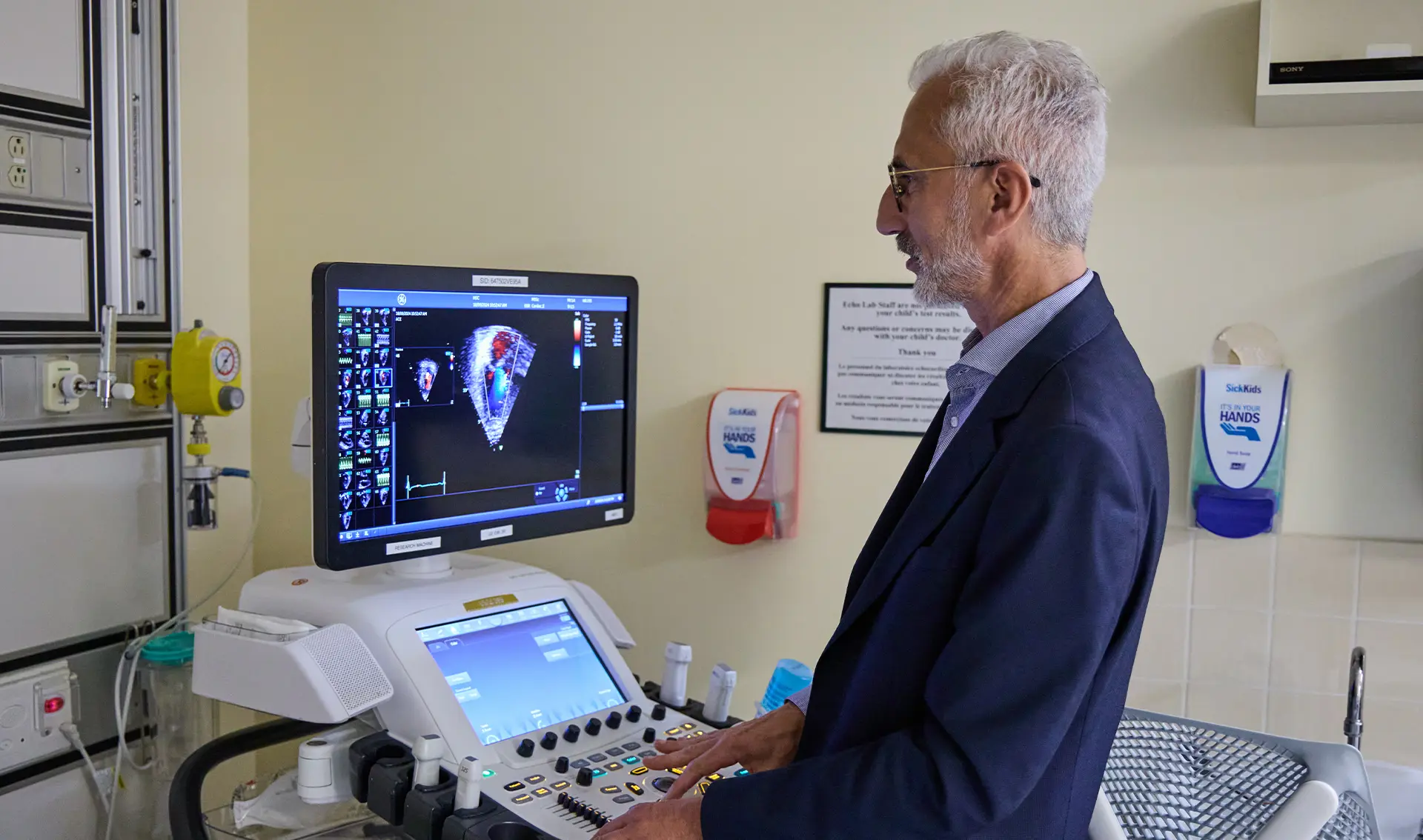

“We work hard every day to offer the best possible life to patients. The efforts have resulted in significantly improved survival rates,” says Dr. Luc Mertens, medical director of echocardiography and co-director of the pulmonary hypertension programs at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto.

“Our next task is to become better at reducing the complications and improving the quality of life through the lifespan,” says Dr. Mertens, who did much of his medical training in Belgium. He came to Canada and joined the SickKids team in 2008.

The key to survival is a surgery called the Fontan procedure, usually performed in early childhood. It reroutes the circulation so oxygen-poor blood coming back from the body travels directly through the lungs on its way back to the heart. The single ventricle then pumps out the re-oxygenated blood to the body.

Over time, however, more than 30% of people get sick, developing what is called Fontan associated circulatory failure (FCF). Their capacity for physical activity may decline to the point that simple tasks of daily life leave them breathless. Treatment options are very limited; for many, a heart transplant is the only solution.

Dr. Luc Mertens is the medical director of echocardiography and co-director of the pulmonary hypertension programs at the Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto.

Dr. Mertens and his research assistant studying their computers.

Why does FCF affect some people but not others? How could it be prevented?

Those are the questions driving a multidisciplinary research project led by Dr. Mertens. It’s called PHUR4Life — Precision Health for patients with Univentricular HeaRts across the Lifespan. And in 2024, it received one of three Congenital Heart Disease Team Grants, co-funded by Heart & Stroke donors, together with Brain Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

“It’s very rewarding to see how patients thrive,” says Dr. Mertens, “but at the same time heartbreaking when Fontan failure occurs at the time where they should live their lives to the fullest.”

Chapter 2 Lifelong impact

While survival rates for such babies were poor in the past, that’s improved dramatically in recent years. A 2024 study found risk of death in the first year of life was 36% for those born between 1970 and 1981, but improved to just 8.7% for those born between 2006 and 2017.

Dr. Mertens says 85% of people reach adulthood after a Fontan procedure — he now sees patients at Toronto General Hospital who are in their 50s. While all of them must cope with many effects of their condition, such as tiring easily with exercise, some patients – for reasons no one understands yet – develop FCF.

“We hope to be able to better identify the mechanisms leading to Fontan circulatory failure and to try to identify early markers,” says Dr. Mertens.

The research team will use four decades of data to create a detailed picture of the progress of more than 2,000 Fontan patients over their lifespan. “We will look at what makes them feel good and what makes them sicker over time,” Dr. Mertens says.

They will also study genetic factors and use advanced imaging to understand the impact of changes such as stiffening of the heart muscle and changes in the small vessels in their lungs.

Chapter 3 Not just the heart

How someone fares over many years with a cardiovascular condition is influenced by many factors. That’s why Dr. Mertens wants to look at whole-body health, social and other factors as part of the study.

“It has become increasingly obvious that congenital heart disease is a condition that affects the whole person, not just the heart,” says Dr. Mertens. “It impacts the families they are born into and the environment they grow up in. The disease affects the whole person through its impact on neurocognition, mental health and higher risk of early dementia and other problems.”

Dr. Luc Mertens and his team want to help reduce complications and improve the quality of life from childhood to adulthood and beyond.

His study is looking at factors such as where someone lives, their gender and how that impacts their health over the years. “There are so many other factors that remain unstudied.”

Dr. Mertens is determined to help patients with this rare but life-changing condition live their lives to the fullest. By detecting FCF earlier and identifying those at higher risk, he hopes to develop preventive strategies that are targeted to a person’s individual circumstances.

“I think the most important thing we do is deliver hope. When you see what the field has achieved over the last decades, it’s very remarkable. But there’s still a lot of work to do.”

- Learn more about recovering from heart disease

- See how your donation is impacting lives

Related stories

Strength runs in the family

Sophie Bessette’s daughter inherited her heart condition — and her fierce determination to live without limits

Lifelong care for congenital heart disease patients

Children with congenital heart disease are now growing up. Dr. Andrew Mackie wants to ease their transition to adulthood

Saving baby Nora

Thanks to a heart transplant at five months, she’s beating congenital heart disease.