Hope for a rare heart condition

Chapter 1 A medical mystery

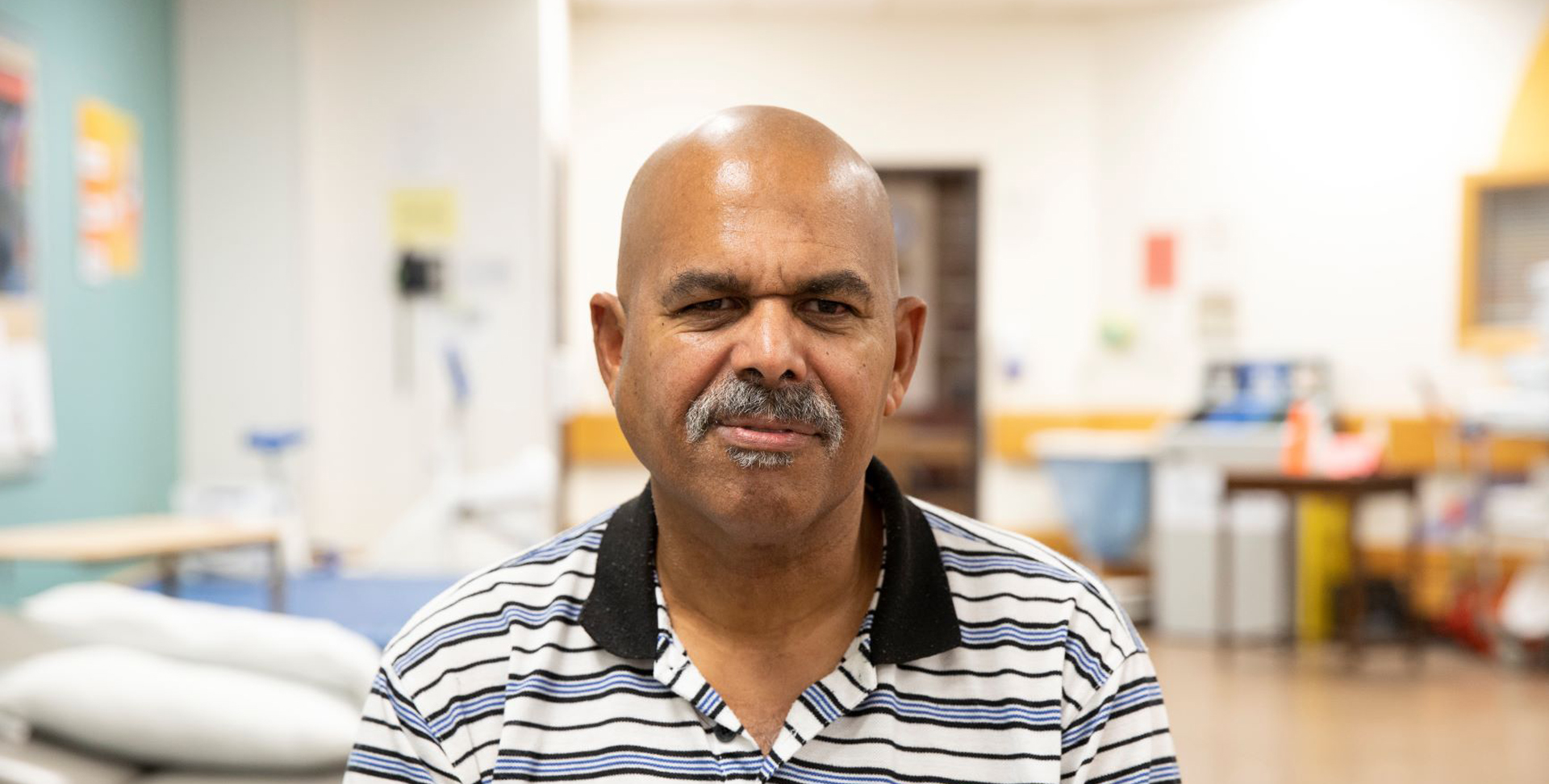

When John Pasternak headed to Kelowna, BC, to golf with a group of fellow physicians, he hoped he could keep up. He felt breathless while climbing stairs — at 62, he knew he could be in better shape — and was hampered by pain from arthritis. He took anti-inflammatories, rented a cart and headed out to the links.

But John’s ankles started swelling and then his abdomen too, plus he became increasingly short of breath. He could barely walk from the golf cart to the tee. After three days he went to the local emergency room.

His blood pressure was through the roof and a doctor suspected he had both heart and liver failure. They adjusted his medications enough to get him home to Medicine Hat, Alta., where he promised to get a proper diagnosis.

Fast forward a couple of months through consultations with his family doctor and a cardiologist. They were trying to make sense of John’s symptoms, which included a previous bout of carpal tunnel syndrome and numbness in his feet. Finally, tests revealed that he had a rare and dangerous condition called cardiac amyloidosis (CA), which causes heart failure. It’s sometimes called stiff heart syndrome.

Chapter 2 The great masquerader

“We call it the great masquerader, or say it’s hiding in plain sight,” says Dr. Nowell Fine, a cardiologist and clinical director of the Libin Cardiovascular Institute in Calgary, who treats John. Dr. Fine, a Heart & Stroke funded researcher, explains that CA is rare and easily mistaken for other types of heart disease.

“We think there are a lot of people walking around in the community with this disease who are under-diagnosed,” says Dr. Fine. “We’re still at the tip of the iceberg.” There are no reliable statistics for CA in Canada or elsewhere.

Wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR) — caused by dysfunction of a protein called transthyretin — which John has, is the more common type of CA. It mostly affects older men and can show up first as carpal tunnel syndrome. Dr. Fine treats about 200 patients with wild-type ATTR CA.

The second, rarer type is called hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. It’s caused by genetic mutations of the transthyretin protein and can affect the heart, nervous system and more. Dr. Fine treats about 20 people with this variation.

Chapter 3 New treatments, new hope

“We had no approved treatments until recently,” says Dr. Fine. Patients often survived just three to five years with wild-type ATTR CA.

Then John learned in 2019 that he could take part in a clinical trial for a new medication that binds to the transthyretin protein, stabilizing it and stopping it from changing into amyloid plaques and harming organs. It does not reverse damage that’s already happened, says Dr. Fine, but it seems to help prevent further problems.

Dr. Fine says there are many other medications in development too. “It’s amazing for a rare disease to be the focus of this much research and progress,” he says. He is helping launch the Canadian Registry for Amyloidosis Research, to determine how prevalent CA is and organize more research.

Today John’s blood pressure has stabilized, he can climb stairs without feeling breathless, and he’s able to work. He has closed his own family practice and now works as a surgical assistant, which he loves. At 65 he can ski and play golf. “I play with a power cart. I can get around the course and I still enjoy myself.”

Related stories

A new heart at 14

Using genetics to beat heart attacks