A life-saving revolution

Stroke treatment has changed dramatically in 40 years. It all started when a couple of neurologists made a phone call.

Chapter 1 An emergency unfolds

Nathan Pryor couldn’t pick up his water bottle. He was at a Halifax gym for his daily CrossFit workout. But suddenly, his hand wouldn’t grasp the bottle. Instead he kept knocking it over.

Within moments Nathan, then 38, could barely move his left side. One of the trainers, who was training to be a paramedic, saw him struggling and recognized the signs of stroke. She called 9-1-1.

The ambulance got Nathan to Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre in minutes. The paramedics had alerted the stroke team, who were waiting and quickly got Nathan a CT scan. It confirmed he was having a stroke, caused by a large clot blocking blood flow in his brain.

The team set up an intravenous line to get Nathan started on thrombolysis, a drug treatment that can break up blood clots and stop or even reverse the effects of stroke.

But Nathan was struggling to speak and couldn’t feel or move his left side.

This happened in 2018. From the first signs of Nathan’s stroke, treatment happened about as quickly as it possibly could. But would that be enough to save him?

Chapter 2 Revolutionary ideas

Just a generation ago, things looked very different, says Dr. Frank Silver, former medical director of the stroke program at Toronto’s University Health Network and a pioneer of stroke care in Canada.

In the 1980s and early ‘90s, stroke was a leading cause of disability for adults, but there was no treatment and very little that could help patients. Sometimes, Dr. Silver had to defend his decision to specialize in stroke neurology. “People would say to me, ‘There’s nothing you can do for stroke, so what’s the point?’”

Luckily, that gloomy outlook wasn’t shared by Dr. Silver and a small group of doctors armed with some revolutionary ideas around stroke care. In just a few decades their ambitious work, supported by Heart & Stroke, has changed what happens when someone has a stroke — before, during and after.

Nathan Pryor benefitted from the latest treatments when he had a stroke at age 38.

With 1.9 million brain cells lost every minute from onset, stroke is a medical emergency.

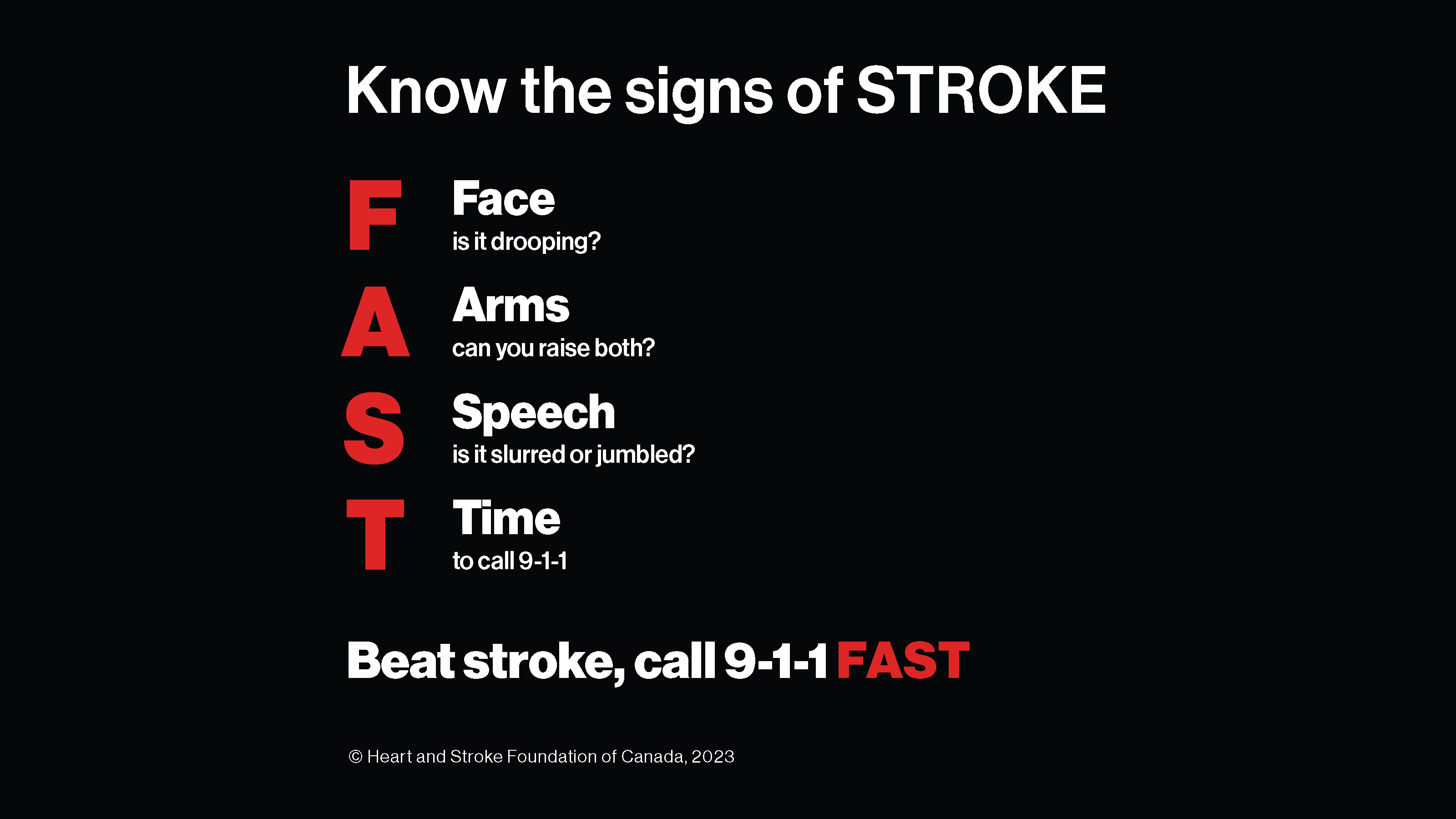

FAST is an easy way to remember key signs of stroke.

In a normal day, your heart pumps about 7,500 litres of oxygen-rich blood through your body. About 20% of that blood needs to funnel directly to the brain to keep it working properly.

Disruptions in that flow can lead to stroke. About 85% of strokes are caused by a blood clot that blocks blood flow; that’s called an ischemic stroke. Less common is hemorrhagic stroke, where a weakened blood vessel breaks open and causes uncontrollable bleeding.

Research shows that 1.9 million brain cells are lost every minute after a stroke begins.

How could this damage be stopped? A potential game-changer arrived in the form of thrombolysis — drug treatment that can dissolve blood clots. It was originally used to treat heart attacks. By 1995 clinical trials were underway to test thrombolysis as a treatment for ischemic strokes. That’s when doctors started to see what they called the “Lazarus effect.”

Like Lazarus rising from the dead, some patients treated with thrombolysis were literally walking away from strokes. The drugs stopped damage to their brains as it was happening. But this effect was only possible if the medication was received within hours of a stroke’s onset.

That posed a problem in the late 1990s, when stroke wasn’t even considered a medical emergency, and few Canadians recognized when someone was having a stroke.

Chapter 3 Awareness is just the start

Dr. Silver, along with a small group of neurologists in Ontario, approached Heart & Stroke to help increase public awareness in the hopes of getting more people with stroke treated fast.

The team’s plan was to teach people how to recognize the signs of stroke. But they soon realized that increased awareness might just fill emergency rooms that couldn’t cope. In order to reduce stroke deaths and disability, the whole healthcare system would need an overhaul.

To treat a stroke fast enough to get the benefits of thrombolysis, a hospital needs a CT scan. More importantly, it needs a specialist available 24 hours a day, to interpret the brain scan and diagnose a stroke. Thrombolysis is a remarkable treatment but it’s not for everyone. Giving it to someone with hemorrhagic stroke (bleeding in the brain) could be a fatal mistake.

Coordinating the equipment and expertise to diagnose and treat stroke fast was a major hurdle.

Acute stroke treatments require that a neurologist on call is available to treat patients at any hour. That was a sticking point for some specialists — it was too much of a culture shock. Unable to persuade every hospital across Ontario to launch a stroke program, the team developed a plan to establish three pilot stroke centres, in Kingston, London and Hamilton, with a fourth site added in Toronto soon after.

But now they faced another hurdle: a rule that forced ambulances to transport patients to the nearest hospital, regardless of what services were available there.

Heart & Stroke worked with ambulance and paramedic services to write new protocols around patient transportation. Now, when stroke was suspected, first responders could bypass a local hospital and take a patient straight to a stroke centre.

Soon enough, the four pilot centres were seeing positive results. “The evidence was overwhelming,” says Dr. Silver. “Interventions improved outcomes, reduced mortality, and increased their chances of returning home — all without increasing the length of (hospital) stay.”

The next challenge was to move beyond the pilot sites. Stroke care would need more funding. The team just needed to get the idea in front of the right people.

Chapter 4 Selling the vision

In early 2000, Mary Lewis, then director of government relations at Heart & Stroke , had the idea to approach Toronto’s Empire Club, which has a history of attracting top-shelf speakers, from Bill Gates to the Dalai Lama.

Dr. Frank Silver didn’t have the household name that the club usually courted. But when he spoke there in March 2000, alongside two prominent stroke survivors, people listened. Six weeks later, the Ontario budget was unveiled with $30 million to develop and staff more stroke centres in Ontario.

Soon another Heart & Stroke researcher, Dr. Antoine Hakim, applied for a grant to create the Canadian Stroke Network (CSN), a forward-thinking organization that would, in partnership with Heart & Stroke, roll out stroke care to the rest of the country.

Launched in 2000, CSN developed Canada’s first Stroke Best Practice Recommendations. The guidelines pulled together the latest, evidence-based recommendations on stroke prevention, diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation. Since the first edition in 2006, they have come to be relied on by healthcare professionals around the world.

CSN also provided seed money for Telestroke, an innovative program led by Dr. Silver that uses video conferencing to connect hospitals in smaller or remote communities with stroke neurologists.

When stroke is suspected, the neurologist can view the patient’s brain scan and advise the local medical team on treatment. That immediate access, studies have shown, saves lives as well as healthcare dollars.

When CSN wound down in 2014, Heart & Stroke stepped in to maintain the Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations.

The timing couldn’t have been more perfect. Soon came the biggest breakthrough in stroke care since thrombolysis.

The ESCAPE trial was led by Heart & Stroke researchers Dr. Michael Hill and Dr. Andrew Demchuk along with Dr. Mayank Goyal, all at the University of Calgary. They used high-tech imaging and a device inserted through the patient’s blood vessels to physically remove a blood clot and restore blood flow to the brain. The procedure, endovascular thrombectomy (EVT), cut the death rate from major ischemic stroke by 50%, and dramatically reduced rates of disability.

The findings were incorporated into the Best Practice Recommendations within weeks and quickly changed the way stroke was treated in Canada and beyond.

Heart & Stroke’s vast network means that emerging evidence like ESCAPE can be quickly delivered into the hands of healthcare professionals who care for stroke patients, says Dr. Patrice Lindsay, director of health systems at Heart & Stroke. This ensures stroke patients in Canada receive the right treatments in the right setting and at the right time, which can lead to a better recovery.

Plus, she adds, Heart & Stroke monitors the quality of stroke care delivered in Canada, another way to promote continual improvements so that Canada’s stroke systems are world-class.

Chapter 5 Surviving and thriving

At QEII in Halifax, the stroke team had performed EVT on about 200 patients by the time Nathan Pryor arrived by ambulance that July day in 2018.

As thrombolytic medication dripped into his arm, the team determined he could benefit from EVT and got him ready for the procedure.

“Immediately after EVT, I regained feeling,” Nathan says. He gave thumbs up to the doctor who performed the procedure, who became quite emotional to see the quick impact. By the next day Nathan felt well. He was supposed to stay in hospital for a week but was discharged a few days later. After another month he was back at work, running his wine importing agency.

Today Nathan experiences some continuing effects of his stroke; his left hand shakes slightly and his gait can be unsteady. But he feels lucky to have escaped severe impacts.

“The take-away for me is that stroke can happen to anyone and what is most important is that people recognize the signs and know that it is crucial to get treatment quickly. That is why I did not have severe damage. My treatment was about as quick as it could be.”

That type of turnaround, says Dr. Silver, is what’s most rewarding about this pioneering work that began all those years ago. “Our stroke team rushes in, and you do see these patients who are very incapacitated because of their stroke and at the end of their treatment they’ve made an excellent recovery.”

Heart & Stroke’s Dr. Lindsay adds that there is integrated stroke care across Canada, and systems are in place to do our best for most people with stroke. Plus, stroke research holds promise for even more progress to come.

Join the fight to end heart disease and stroke.